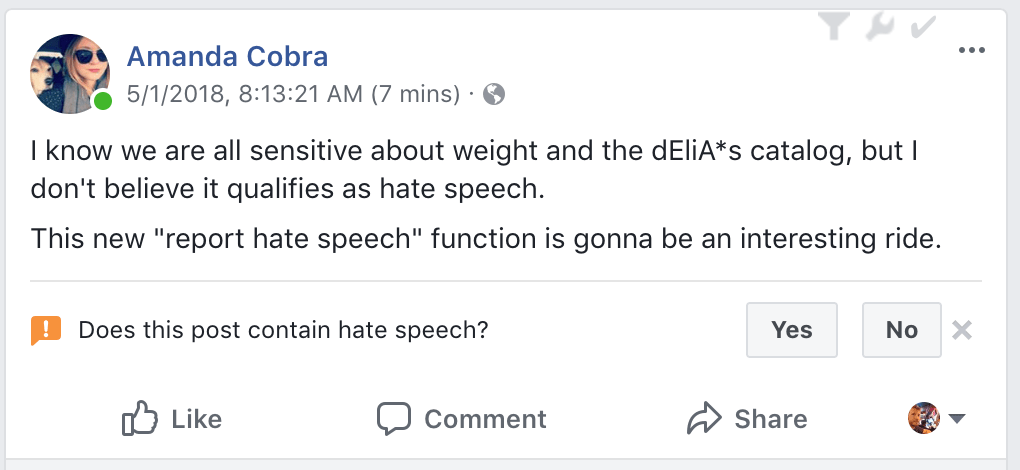

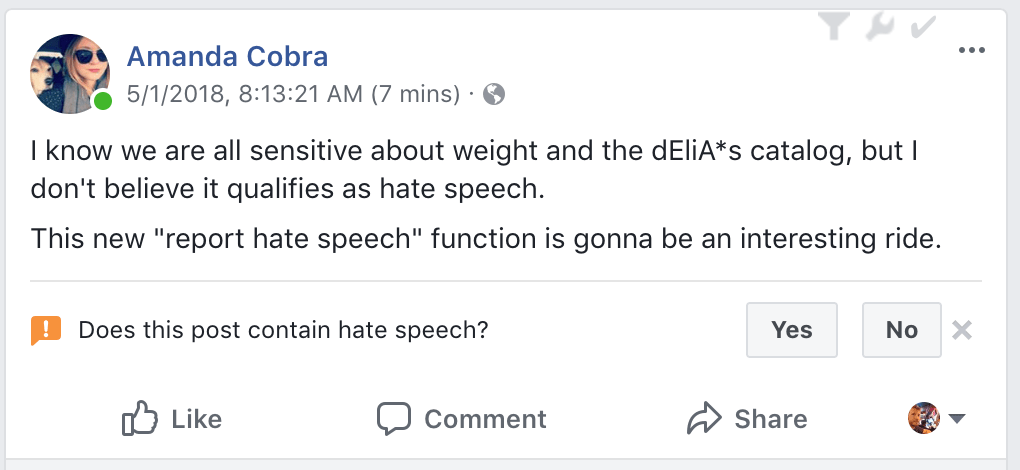

I’ve been planning to write again about Facebook’s efforts to censor its major product: what people post. Facebook is rolling out so much at once, though, that it’s hard to keep up, and harder to craft the lengthy posts necessary to understand the impact of today’s technology on First Amendment advocacy questions. But today’s Facebook screwup, asking people if every news item or post is “hate speech,” has to be explained in historical and technical context to understand how massively injurious it will be.

(From Ars Technica)

[Update: Facebook has now responded that this was not a “mistake” per se. Vice-President of Product Management Guy Rosen said that it was “a test and a bug” which was visible for only 20 minutes. Nverse‘s Danny Paez points out, quite reasonably, that “A prompt like “Does this contain hate speech?” may seem silly when it’s under something benign, but it could be a way for the company to train an algorithm to think more like a human.” But the rest of my much longer post below is that “do we want machines to think like humans? Not if we don’t want human biases incorporated in our algorithms.”]

[More Updates: Wired offers an opposing view, asking for more human intervention but recognizing a role for AI, from a researcher who has studied hate speech. And C|Net offers a report from yesterday’s F8 Facebook conference on Facebook’s AI programs. “‘We have a lot of work ahead of us,’ Guy Rosen, vice president of product management, said in an interview last week. ‘The goal will be to get to this content before anyone can see it.'”]

In short, Facebook appears to be promoting a “reform” that will lead to increasing amounts of public incivility and possibly unfounded and unsupportable regulation.

Exactly the opposite of what it says it wants. And decidedly unscientific.

Some of what Facebook has done is at least arguably reasonable. Their attempt to define “community standards” is far better than Justice Potter Stewart’s “I know it when I see it” standard for obscenity. Jacobellis v. Ohio, 384 U.S. 184, 197 (1964). When you remember that Facebook’s anonymous drafters have to deal across many different cultures with different levels of awareness, most of its community standards make sense.

The best way to understand what Facebook is up to now, however, is to watch a Roomba robo-vacuum explore and clean a room for the first time. It starts out spinning in a circle for a while, then tentatively bumps out in one direction until it hits something, spins again and moves somewhere else, and so on, for an amazingly long time compared to a human “sanitary engineer,” who simply looks, recognizes and vacuums. It is the beginning of a search by a machine (or those responsible for machine thinking) for a path through the typically-chaotic environment created by unpredictable humans. Another example is how robot engineers learned that children near a robot were a highly-dangerous environment — for the robot, which had to be protected from the kids.

Many people looking at how to police “harmful speech,” Mark Zuckerberg included, talk about “AI” (Artificial Intelligence) being the holy grail of dealing with vast amounts of speech, hateful or otherwise. And the latest “flavor of the month” in AI for this topic is “machine learning.” Machine learning is simply asking a machine to analyze massive amounts of data to predict future outcomes.

Machine learning is, in fact, likely to be a very good way to look at human speech and actions to identify root causes of later actions that may not be intuitively and immediately obvious. Because they are not subject to “confirmation bias,” primacy, perseverence, and many other human tendencies to misread or ignore evidence, well-programmed machines can start with a blank slate, looking for correlations and factors that would likely elude even determined human observers.

I’m not unsympathetic to the difficulty of Facebook’s self-imposed goal. I started “coding” in the 1960’s, as part of a California effort to promote computer and science literacy at an early age (I think it backfired in my case; I did go to college in astrophysics, but ended up a mildly-libertarian First Amendment lawyer). I have always had clients who are among the most advanced in data collection, analysis, and machine learning for use in advocacy and political activity.

You can, for example, view the movement of computer-aided analysis in advocacy in three stages: looking at the past to predict the future -> looking at the present to predict the future -> using mathematics to predict the future. In the early days of computer analysis, we looked to see cause and effect in the past. For example, we mailed (snail-mailed in those days) to a list of members of an organization that looked like ours, based on perceived characteristics; if we got a good return from that mailing, we did it again (and if we were smart, we cross-checked among lists to find newer and better lists to mail). Back in the 1970’s, the Democratic National Committee had me learn from Matt Reese, the “father of microtargeting” these lists.

Looking at the past was mostly human-guided. We looked at the results of prior tests and paid a lot of money to experts who said they could tell us what they meant. But predicting future results was mostly guesswork. And, of course, distorted by the same biases that humans — even well-trained humans — are always subject to.

In the present, better technology has given us almost real-time results of tests. The Trump and Obama campaigns were very good at this. With massive scale and advanced technology, those data teams could target millions of fundraising and political appeals with vastly-improved precision. But it was still brute-force guesswork, for the most part, with human predictions driving analyses, which then produced more human-guided predictions.

An example: Cambridge Analytica’s “psychographic modeling” behavior. In effect, automating “psychohistory” in author Isaac Asimov’s 1950’s Foundation trilogy, algorithms that can predict human history for hundreds of years in the future. The popular OCEAN psychographic model technique was developed in the 1980’s. And it was pretty much what Matt Reese and programmer Jonathan Robbin were doing with “Claritas” in the 1970’s, categorizing mailing lists as being of “clusters” of people likely to respond to particular messages. More importantly, this type of modeling, though based on computer-aided analyses and much more accurate than earlier methods, is still subject to human biases, both in analyses of massive data and predictions based on the analyses.

Enter the (predicted and sometimes here) third wave: removing humans from the prediction process. Machine learning. Develop the algorithms necessary for the computers themselves to review the data and make predictions from it. Taking humans out of the process allows insights such as the famous “political ideology can be predicted by sales of frozen dinners.” Which is, in fact, true, if incomplete.

What is missing from most analyses of machine learning is an understanding of what separates good from bad machine learning. If all the machines do is take a quick snapshot of what’s happening, the resulting analyses are likely to be no better than what Reese and Robbin were doing five decades ago. The predictions from those analyses will be very accurate — for a very short time and in limited circumstances. The use of static machine learning analyses is simply another form of human bias: “it came from a computer, so it must be true.”

Accurate modern machine learning is an “iterative” and constantly-changing process. If analyses of data are improved by removing human biases, so are analyses of data analysis algorithms and models. And one of the elements of improved algorithms is their maintenance and improvement over time. Feedback and testing are requirements for any machine-learned result, and more importantly, for any machine-learning algorithm. What we might have felt was accurate in 2015 was likely proven wrong in 2017.

Today’s obvious Facebook mistake is not just a reversion, it’s a demonstration of exactly the wrong way to go. The trend in predicting human issue and political positions is, as shown above, to move beyond human biases. Today, Facebook mistakenly rolled out a tool that not only solicits human bias, but uses it to silence the speech of others.

Facebook is going to ask readers of its newsfeed to click a box if they think something is “hate speech.” Facebook’s Community Standards define “hate speech” as:

We do not allow hate speech on Facebook because it creates an environment of intimidation and exclusion and in some cases may promote real-world violence.

We define hate speech as a direct attack on people based on what we call protected characteristics — race, ethnicity, national origin, religious affiliation, sexual orientation, sex, gender, gender identity, and serious disability or disease. We also provide some protections for immigration status. We define attack as violent or dehumanizing speech, statements of inferiority, or calls for exclusion or segregation. We separate attacks into three tiers of severity, as described below.

Sometimes people share content containing someone else’s hate speech for the purpose of raising awareness or educating others. Similarly, in some cases, words or terms that might otherwise violate our standards are used self-referentially or in an empowering way. When this is the case, we allow the content, but we expect people to clearly indicate their intent, which helps us better understand why they shared it. Where the intention is unclear, we may remove the content.

Do they really expect people to read and understand that particular definition before they click “yes” or “no?” Or is it more likely that people will just call everything they don’t like “hate speech?”

Facebook is a private company, not a government subject to the First Amendment. In that context, Facebook is perfectly entitled to define hate speech as whatever it feels like. But, as Guidestar (which publishes copies of tax filings by tax-exempt entities) found when it tried to flag three dozen organizations as “hate groups,” mistakes can happen. Imagine your outrage if someone wrongfully accused you of being a “hate group.” Guidestar won a costly legal battle, but its new chief executive Jacob Harold “acknowledged that there were reasonable disagreements about the fairness of some of the hate-group labels.”

And, in fact, Facebook admits that mistakes have happened at Facebook’s existing “hate speech” monitoring process. ProPublica, a journalistic advocacy organization, reported in December 2017 that when it asked Facebook about 49 seemingly offensive examples of “hate speech” that remained visible, Facebook replied that 22 of the 49 decisions were “the wrong call.”

Facebook is much, much larger and stronger than Guidestar. It can undoubtedly withstand the thousands of lawsuits likely to arise from its labeling of posts as “hate speech.” But its legal position is far weaker than Guidestar’s; Guidestar won its lawsuit because it was not deemed to be engaging in “commercial speech.” Facebook won’t have that protection.

But even more important, if Facebook’s halting and mistaken efforts to use “crowdsourcing” to determine whether particular posts or ads are “objectionable content” are any indication, Facebook is headed down the wrong AI path. As shown above, modern AI analyses, especially involving machine learning, as Facebook appears to be doing, take OUT the human element, using objectively measurable standards rather than innate human biases. Facebook is doing the opposite.

By proceeding in an unscientific and biased manner, Facebook itself is encouraging a finding of “hate speech,” and thus slanting not only its actions, but likely also the reporting of how much “hate speech” actually exists. Just asking the question of humans is very likely to trigger a much higher level of positive reporting, a well-recognized phenomenon known as the “observer-expectancy” effect. Because the question is asked, and a reporting option offered, readers will think that someone must have thought it was hate speech to even ask about it. This is a “positive feedback loop” that will likely have unexpected and probably unpleasant consequences.

Again, I understand that this was a preliminary effort, and Facebook has been candid that in other countries, relying on posts to determine whether language can be “coded” threats is useful. But Facebook’s own history, as well as the well-reported development of analytical techniques using Facebook’s own type of technology, demonstrate that having people self-report “hate speech” is likely to over-report and under-report, as well as mis-report, objectionable speech. Even worse, it is probably equally likely to censor or restrict legitimate speech that someone just doesn’t like.

And that doesn’t seem at all within Facebook’s own community standards or announced mission.

You must be logged in to post a comment.