This month’s AI-influenced image is of Associate Justice Sandra Day O’Connor, who passed away at 93 of complications from Alzheimer’s disease on December 1, a particularly cruel ending to a life lived fully and meaningfully. Among her many important contributions (besides being the first woman to sit on the Court) were decisions involving the First Amendment, including those establishing the “speech spectrum” as an organizing principle for determining government’s power over speech (see first topic below). This version of her latest official portrait was created using the 2023 version of Corel Painter, with a style based on John Singer Sargent, perhaps the greatest American portraitist.

GOVERNMENT CENSORSHIP OF ALLEGED “DISINFORMATION:”

25 Years Before Murthy and Vullo, The Supreme Court Considered Similar Cases About First Amendment Limits on Government Speech: This Term, the Supreme Court of the United States has taken up the question of whether government officials can do indirectly what they cannot do directly: silence critics by pressuring their providers of essential infrastructure such as social media platforms that publish their speech or banks and insurers who allow their organizations to exist. Both Murthy v. Missouri, No. 23-411, and NRA v. Vullo, No. 22-842, are government indirect censorship cases currently being considered by the Supreme Court, with oral arguments planned in March 2024. Those decisions, likely to be handed down before July, could rest on a doctrine announced in 1996 in a very similar case.

Before social media, there were Letters to the Editor and op-eds. Keen Umbehr, who had a trash-hauling contract with Wabaunsee County, Kansas, wrote many of those pre-Internet missives in his local newspapers, mainly criticizing the County Commissioners for mismanagement. The Commissioners were not pleased, and threatened the official county newspaper if it published any more of Umbehr’s criticism. Given the available technology of the time, this indirect censorship effort is very similar to the government attempts to suppress criticism by threatening essential infrastructure providers in both the Murthy and Vullo cases. Eventually, the County rescinded its trash contract with Umbehr. Umbehr sued for unconstitutional retaliation under the First Amendment and won. Board of County Commissioners, Wabaunsee County v. Umbehr, 518 U.S. 668 (1996).

Among other things, the Umbehr decision described a new and useful way to think about government power over speech: a “speech spectrum” running from government’s own speech through official actions, through government employees’ speech, to government contractors and representatives, to private citizens. Under the speech spectrum, government has the most power over its own expression, that of government officials speaking within their authority, and the speech that it pays for. At each step away from government itself, however, government’s power to restrict expression weakens, until it reaches speech by private citizens, which “the government has no legitimate interest in repressing”:

Our unconstitutional conditions precedents span a spectrum from government employees, whose close relationship with the government requires a balancing of important free speech and government interests, to claimants for tax exemptions, users of public facilities, and recipients of small government subsidies, who are much less dependent on the government but more like ordinary citizens whose viewpoints on matters of public concern the government has no legitimate interest in repressing.

Umbehr, 518 U.S. at 680 (cleaned up).

Both Murthy and Vullo include defenses and assertions by the government officials and agencies involved about the “government speech doctrine,” which permits the government to choose its own speech when it or its representatives speak, even about controversial or political public policy topics. Both the Federal Petitioners in Murthy and New York State official Respondent in Vullo claim that their “jawboning” or “blackmail” efforts were simply government officials speaking in an effort to persuade their targets, rather than unconstitutional “coercion” of unwilling participants. The Second Circuit opinion in Vullo, for example, does the same: “Two sets of free speech rights are implicated [in this case]: those of private individuals and entities and those of government officials. With respect to the latter, the First Amendment does not impose a viewpoint-neutrality requirement on the government’s own speech; a government official has the right to speak for herself (and her agency) and to select the views she wishes to express.” Nat’l Rifle Ass’n v. Vullo, 49 F.4th 700, 714-15 (2nd Cir. 2022).

There is much merit in the “government speech doctrine,” since “Government has no mouth, it has no hands or feet; it speaks and acts through people. Government employees must do what the state can’t do for itself because it lacks corporeal existence; in a real sense, they are the state.” Arizonans for Official English v. Yniguez, 69 F.3d 920, 960 (9th Cir. 1994)(Kozinski, C.J., dissenting), vacated as moot, Arizonans for Official English v. Arizona, 520 U.S. 43, 48-49 (1997). This is the original basis of the judicially-created “government speech doctrine:” government has the right to control what it and its employees say and what it pays for. “When government speaks, it is not barred by the Free Speech Clause from determining the content of what it says.” Walker v. Tex. Div., Sons of Confederate Veterans, 576 U.S. 200, 207-08 (2015). “Indeed, it is difficult to imagine how the government could function if it lacked this freedom” to express its views on matters of public policy. Pleasant Grove City v. Summum, 555 U.S. 460, 468 (2009).

The government speech doctrine, however, does not entirely displace the First Amendment. For example, two paragraphs after the quote above, the Summum Court also said: “This does not mean that there are no restraints on government speech. For example, government speech must comport with the Establishment Clause. The involvement of public officials in advocacy may be limited by law, regulation, or practice.” 555 U.S. at 468. (Summum was a case about placing religious symbols on public property.)

There were other “speech spectrum” cases in the same era, including Waters v. Churchill, 511 U.S. 661, 671-675 (1994). “The key to First Amendment analysis of government employment decisions, then, is this: The government’s interest in achieving its goals as effectively and efficiently as possible is elevated from a relatively subordinate interest when it acts as sovereign to a significant one when it acts as employer.” 511 U.S. at 675 (emphases added). Thus, government may take and promote its own position without infringing the rights of persons who disagree or wish to exercise their own free speech rights. Regan v. Taxation With Representation, 461 U.S. 540, 549 (1983) (First Amendment rights to petition government do not require government to provide tax deduction).

But it is overstatement to say, as the Second Circuit decision under review in Vullo suggests, that the First Amendment never applies to government’s speech. Rumsfeld v. Forum for Academic and Institutional Rights, 547 U.S. 47, 59 (2006) (“the First Amendment supplies ‘a limit on Congress’ ability to place conditions on the receipt of funds’”); Umbehr, 518 U.S. at 680 (“The First Amendment permits neither the firing of janitors nor the discriminatory pricing of state lottery tickets based on the government’s disagreement with certain political expression.”); Shurtleff v. Boston, 142 S.Ct. at 1595 (Alito, J., concurring)(“the real question in government-speech cases [is] whether the government is speaking instead of regulating private expression…”).

What the speech spectrum cases would ask in both Murthy and Vullo is whether the government official involved was commanding as a sovereign, even if calmly and indirectly, or whether she was participating in the marketplace of ideas like any other speaker. Waters v. Churchill, 511 U.S. at 675. In both the federal and state cases now before the Supreme Court, the government was trying to silence critics, not productively discuss public policy issues.

Time to File Supreme Court Briefs in Murthy v. Missouri (Formerly Missouri v. Biden) Extended: On October 20, the Supreme Court of the United States agreed to review Missouri v. Biden, (5th Cir., No. 23-30445, September 8, 2023), a challenge to two lower court decisions holding a vast federal government effort to censor social media posts that government officials considered to be “misinformation” violated the First Amendment. Because the Court’s grant of certiorari took the case off the “emergency docket,” the Court gave it a new name and case number: Murthy v. Missouri, No. 23-411. President Biden, who was named in the original complaint, was not bound by the lower courts’ injunction against censorship, leaving U.S. Surgeon General Vivek Murthy as the signature Petitioner in the Court’s review.

On December 1, as expected, the Solicitor General, with the agreement of the State and private Respondents, asked the Court to extend the time for the Federal Petitioners to file their Opening Brief on the merits to December 19 and the time for the Respondents to file their Opening Briefs to February 2, 2024. The Court granted the request, which under Supreme Court Rule 37.3 means that the deadline for filing amicus curiae briefs (seven days after filing of the briefs of the party supported) is also extended. This briefing schedule would allow oral argument in this case to be heard in March 2024, in time for the Court’s usual “finish before July” deadline for a Term.

Supreme Court Asked to Allow Other Victims of Federal Government Censorship Effort to Intervene in Murthy: Meanwhile, some of the “Disinformation Dozen” controversial social media participants censored in the government censorship effort debated in Murthy, including erst-while Presidential candidate and avowed skeptic of vaccinations Robert F. Kennedy, Jr., filed a Motion to Intervene in the Murthy case. Their argument for intervention is vulnerable on procedural grounds; the “Disinfo Dozen” contend that they are the speakers and writers whom the Murthy Respondents seek to listen to, but in so doing, argue, basically, that they and their issues are the same as those who brought the Murthy/Missouri case. Courts, especially the Supreme Court, rarely allow intervention without a showing that the putative intervenors will not be adequately represented in the case, and the granting of certiorari here indicates that the current parties are already adequately representing the issues the Supreme Court wants to hear. The fundamental problem is that freely allowing such intervention risks flooding the courts with copycat pleadings without any compensatory jurisprudential benefit.

Plus, the “Disinfo Dozen” waited too long before filing their Intervention Motion; the Supreme Court rarely permits intervention after granting a Petition for Certiorari. The factual record in the case is set already, the briefing schedule is already fully underway, and any further delay would crowd the Court’s deadline. Any unique legal issues raised by intervenors could easily be handled in an amicus brief.

Both the Federal Petitioners and State and private Respondents have opposed the intervention motions, and the “Disinfo Dozen’s” Reply Brief to the opposition nitpicks arguments rather than facing their own fundamental pleading weaknesses. Still, as discussed in last month’s Public Policy Advocacy Highlights, the Court has sought other views in this case by granting certiorari in a similar case involving New York State’s censorship of an exempt organization by forcing the organization’s bankers and insurers to drop the organization as a customer (see next topic below).

Supreme Court Petitioner’s and Amici Briefs In NRA v. Vullo, No. 22-842, Due Shortly Before Christmas: After holding onto the Petition for Certiorari (review of a case) in Nat’l Rifle Assoc. v. Vullo, No. 22-842 for weeks, on November 3, the Supreme Court granted cert in the case challenging New York’s “jawboning” (if you’re the govt) or “blackmailing” (if you’re the NRA) bankers and insurers of the NRA. The grant was limited to Question 1 in the Petition, which now reads:

QUESTION PRESENTED:

Bantam Books v. Sullivan held that a state commission with no formal regulatory power violated the First Amendment when it “deliberately set out to achieve the suppression of publications” through “informal sanctions,” including the “threat of invoking legal sanctions and other means of coercion, persuasion, and intimidation.” 372 U.S. 58, 66-67 (1963). Respondent here, wielding enormous regulatory power as the head of New York’s Department of Financial Services (“DFS”), applied similar pressure tactics – including backchannel threats, ominous guidance letters, and selective enforcement of regulatory infractions – to induce banks and insurance companies to avoid doing business with Petitioner, a gun rights advocacy group. App. 199-200 ¶ 21. Respondent targeted Petitioner explicitly based on its Second Amendment advocacy, which DFS’s official regulatory guidance deemed a “reputational risk” to any financial institution serving the NRA. Id. at 199, n.16. The Second Circuit held such conduct permissible as a matter of law, reasoning that “this age of enhanced corporate social responsibility” justifies regulatory concern about “general backlash” against a customer’s political speech. Id. at 29-30. Accordingly, the questions presented are:

1. Does the First Amendment allow a government regulator to threaten regulated entities with adverse regulatory actions if they do business with a controversial speaker, as a consequence of (a) the government’s own hostility to the speaker’s viewpoint or (b) a perceived “general backlash” against the speaker’s advocacy?

Ian Milhauser, no friend of the NRA, wrote about Vullo in a Vox piece:

A foolish state official may have just handed the NRA a big Supreme Court victory … nothing in the First Amendment prohibits New York from targeting illegal insurance that is backed by the NRA, even though the NRA also engages in First Amendment-protected advocacy. But then Vullo did something incomprehensibly stupid.

In February 2018, the Parkland, Florida, school shooting happened — killing 17 high school students and school staff. After this shooting, DFS issued a “guidance,” signed by Vullo, which encouraged insurers to ‘continue evaluating and managing their risks, including reputational risks, that may arise from their dealings with the NRA or similar gun promotion organizations. …It’s not hard to read that guidance as a coercive attempt to punish the NRA because New York’s government disagrees with the NRA’s political advocacy in favor of looser gun laws. … But, by bringing herself and her agency into a political dispute about gun advocacy, Vullo gave this highly partisan Supreme Court an opportunity to insert itself into what should have been a routine insurance enforcement action.

New Research Finds That Censoring Extremists “Only Makes Them More Extreme”: Ricki Schlott writes in the Houston Chronicle (paywall) that

In my new book, “The Canceling of the American Mind: Cancel Culture Undermines Trust and Threatens Us All — But There Is a Solution,” my co-author Greg Lukianoff and I argue that censorship doesn’t actually stamp out bad ideas. … Forcing people from a mainstream platform to a niche platform is a surefire way to insulate them in an echo chamber, where they only hear the opinions of people who agree with them.

Researchers at the Network Contagion Research Institute and the Anti-Defamation League’s Center on Extremism have data to prove that censorship is closely correlated with even more extremism. They found that, when Twitter (as it was known then) purged swaths of accounts over the past several years, alternative social media platforms like Gab, which is popular with alt-right and far-right users, swelled in membership. …

The worst possible way to fight extremism is sending extremists into underground cesspools riddled with positive feedback loops and confirmation bias. People who don’t hear competing viewpoints tend only to descend deeper into a polarization spiral. In retrospect, social media censorship seems to have done little to actually reduce the amount of hatred in the world — and, if anything, just condensed it.

Harvard law professor Cass Sunstein, who coined the “Law of Group Polarization,” put it best: “People who are opposed to a minimum wage are likely, after talking to each other, to be still more opposed; people who tend to support gun control are likely, after discussion [with one another], to support gun control with considerable enthusiasm.” Although social media companies are understandably motivated to squelch out despicable views on their platforms, history has taught us doing so only makes matters worse.

IRS

Federal District Court Denies Summary Judgment to IRS over Whether IRS Can Require Disclosure of Donor Information in Government Reports for 501(c)(3) Organizations: On Nov. 9, U.S. District Judge Michael Watson of the Southern District of Ohio denied a summary judgment motion by the Internal Revenue Service to dismiss the Buckeye Institute’s challenge to the IRS requirement that 501(c)(3) organizations submit an annual Schedule B list of significant donors as part of their annual information return Form 990. Judge Watson found that the 2021 Supreme Court decision in Americans for Prosperity Foundation v. Bonta, 594 U.S. ___, 141 S.Ct. 2373, 2383 (2021), which prohibited “dragnet” collection of Schedule B donor information by the California Attorney General, makes a government decision to require donor disclosure subject to “exacting scrutiny.” “Regardless of the type of association, compelled disclosure requirements are reviewed under exacting scrutiny.” Id. Exacting scrutiny is not the highest level of judicial review, but it’s very tough to meet.

Under the exacting scrutiny standard, “there must be a substantial relation between the disclosure requirement and a sufficiently important governmental interest.” Id. at 2383 (quotation marks and citations omitted). To pass exacting scrutiny, the “strength of the governmental interest must reflect the seriousness of the actual burden on First Amendment rights.” Id. (cleaned up). In addition, although a compelled disclosure requirement need not be “the least restrictive means of achieving [the government’s] ends,” the requirement must be “narrowly tailored to the government’s asserted interest.” Id.

Slip op. at 9.

And Bonta tightened “exacting scrutiny” even more, at least when it comes to donor disclosure. So noted both Law Prof. Rick Hasen and retired Law Prof. Ellen Aprill (an active participant in the First Tuesday Lunch Group). The IRS in this case chose to ignore or deflect Bonta, by repeating its oft-asserted but oft-rejected claim that tax exemption for the organization and deductibility of donations for the donor was a “choice” by the organization that waived the constitutional protections not just of the organization but of the donors. Slip op. at 10.

Judge Watson rejected the IRS’s constitutional “waiver” argument, as the Supreme Court did in Bonta, and in two other recent, and one ancient, Supreme Court decisions: Agency for Int’l Dev. v. Alliance for Open Soc’y Int’l, 570 U.S. 205, 214-15 (2013) (“AOSI I”) (“[T[he relevant distinction that has emerged from our cases is between conditions that define the limits of the government spending program – those that specify the activities Congress wants to subsidize – and conditions that seek to leverage funding to regulate speech outside the contours of the program itself”); Agency for Int’l Dev. v. Alliance for Open Soc’y, 140 S.Ct. 2082, 2086 (2020) (“AOSI II”) (same); Rust v. Sullivan, 500 U.S. 173, 195-200 (1991) (holding that Congress could prohibit recipients of federal funds for a “family planning” public health project from using those funds for anything related to abortion). Slip op. at 10-11.

Applied here, the Disclosure Requirement requires any 501(c)(3) to disclose their substantial donors in order to operate as a 501(c)(3). That is, if a charitable organization does not disclose their substantial donors, they may not receive the benefit of 501(c)(3) status. Thus, this is not an example of the Government “simply insisting that public funds be spent for the purposes for which they were authorized.” Rust, 500 U.S. at 196. Instead, the Government denies its 501(c)(3) tax benefits entirely to organizations that resist the disclosure requirement. Thus, if the Disclosure Requirement is unconstitutional, it would be an unconstitutional condition on receipt of the tax benefits. See id. at 196-97 (explaining that the “‘unconstitutional conditions’ cases involve situations in which the Government has placed a condition on the recipient of the subsidy rather than on a particular [federally-funded] program or service[.]” (emphasis in original)).

Slip op. at 11-12.

So, there’s a factual dispute in this case about whether “the Disclosure Requirement is an important part of the IRS’s enforcement and compliance procedures. On the other hand, Plaintiff raises several issues that undercut Defendants’ arguments. Determining which side is ultimately more persuasive will turn, at least in part, on witness credibility, which is an inappropriate consideration at summary judgment.” Slip op. at 12.

Therefore, Hasen and Aprill were right about the significance of AFPF v. Bonta, and others (including the Public Policy Legal Institute, host of this blog) who believe that Schedule B is both useless and unconstitutional were also right. The Schedule B donor disclosure rules are at best, unsupported dragnets, and at worst, plainly unconstitutional. Judge Watson said, to trial we go, IRS. Summary Judgment denied.

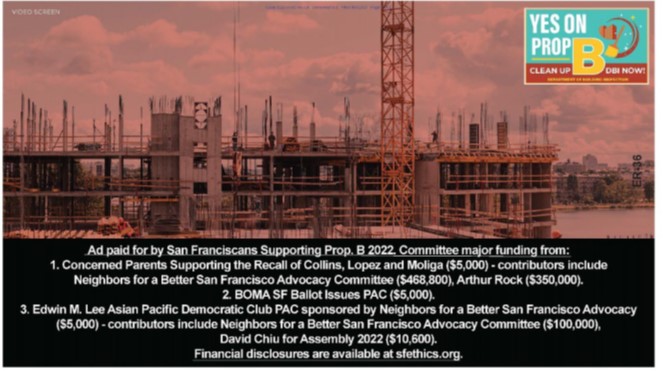

However, the Ninth Circuit in No On E v. Chu, No. 22-15824 (9th Cir. October 26, 2023) (h/t IFS), also agreed on the use of “exacting scrutiny” under AFPF v. Bonta. Then, however, the 9th Cir. panel upheld not only a donor disclosure under a San Francisco ordinance, but also the part of the ordinance requiring the disclosure not just of donors, but of donors to donors (“secondary-contributors”). There was a request for rehearing en banc, but not enough Circuit Judges voted in favor of rehearing. Nine Circuit Judges then signed a dissent from the denial of rehearing which pointed out that the new panel decision “threatens vital constitutional protections and should have been reheard en banc”, because the decision “explicitly allows San Francisco to commandeer political advertising to an intrusive degree that greatly exceeds what our settled caselaw would tolerate in the context of commercial advertising.” Slip op. at 35 (emphasis in original). This led Law Prof. Rick Hasen to predict that the Supreme Court was likely to reverse the Ninth Circuit, and shows there is still some play in the joints of this legal doctrine.

But, simply looking at the pictures of the effect of the extended disclosure requirements in the ad examples reprinted in the Judge Collins-authored dissent (where much of the text of the ad was taken up by the extended compelled disclosures) itself would be likely grounds for summary reversal by the Supreme Court.

New IRS Rules on Requesting Copies of Tax-Exempt Organization Documents: An IRS email reports that:

IRS updates process for requesting copies of exempt organization documents

Looking for information about an exempt organization? Use the Tax Exempt Organization Search (TEOS) tool on IRS.gov. TEOS is the primary source for publicly available data on electronically filed Forms 990 provided by the IRS, and it also allows the public to view determination letters issued since January 1, 2014. Taxpayers can request other information related to tax-exempt organizations using either Form 4506-A or 4506-B. The IRS has updated the process to request copies of these documents, including a revised Form 4506-B. The revised form ensures consistency and improves timeliness for processing these requests. Please see below for specific details on the processes that are now in place to request copies of documents for exempt organizations.

FEC

FEC Releases Directive 74 implementing New Controls on FEC Office of General Counsel as of Nov. 1: The Federal Election Commission has released Directive 74: Investigations Conducted by the General Counsel; Enforcement Investigative Plans, to implement the new rules putting the brakes on independent investigations started or expanded by the Federal Election Commission’s sometimes-rogue Office of General Counsel. Paul Bedard, who writes the “Washington Secrets” column in the Washington Examiner, had a Nov. 10 insider piece. “In a commonsense proposal, a majority of the commissioners this month decided to take control of all investigations into election fraud, a responsibility that over time they had ceded to FEC attorneys. The move comes in the wake of some high-profile embarrassments and revelations of investigations by FEC staff that some commissioners didn’t even know about.” Commissioners Dickerson and Trainor issued a Statement with some graphic examples of OGC mis-steps.

COURTS

New Supreme Court Code of Conduct Getting Mixed Reviews: On November 13, the Supreme Court of the United States released a formal Code of Conduct for Justices, adopted and signed by all nine sitting Justices. Coverage: Washington Post, New York Times, NPR, Law Prof. Josh Blackman in Volokh Conspiracy. There are two parts to the material released today: the Code of Conduct itself (the first ten pages) and a Commentary, similar to explanations to Rules Commentaries in many State court rules.

The new Code of Conduct contains no sanctions or similar penalties for violations and there appears to be no formal structure for adjudicating questions, setting it apart from some similar legislatively-imposed codes on judges. The Code includes a preliminary introductory statement:

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES STATEMENT OF THE COURT REGARDING THE CODE OF CONDUCT

The undersigned Justices are promulgating this Code of Conduct to set out succinctly and gather in one place the ethics rules and principles that guide the conduct of the Members of the Court. For the most part these rules and principles are not new: The Court has long had the equivalent of common law ethics rules, that is, a body of rules derived from a variety of sources, including statutory provisions, the code that applies to other members of the federal judiciary, ethics advisory opinions issued by the Judicial Conference Committee on Codes of Conduct, and historic practice. The absence of a Code, however, has led in recent years to the misunderstanding that the Justices of this Court, unlike all other jurists in this country, regard themselves as unrestricted by any ethics rules. To dispel this misunderstanding, we are issuing this Code, which largely represents a codification of principles that we have long regarded as governing our conduct.*

Some of the specific provisions deal with the interaction between Justices (and their families) and tax-exempt and political organizations. Canon 5, for example, says “A Justice should not engage in other political activity.” But “This provision does not prevent a Justice from engaging in activities described in Canon 4”, which permits a Justice to be involved in fundraising, educational, and civic or charitable activities.

A singular feature of the new Code is what has always driven the Court’s ethics practices: compliance, investigation and disqualification are at the discretion of individual Justices and are not favored because there is no equivalent or alternative forum or participants available if the Justices are recused. The Court notes that it is the head of one of the branches of government, and it wrote the Code and Commentary from that viewpoint. Setting the bar too low would likely be considered handicapping the judiciary as a whole. Thus, the new Code is unlikely to resolve at least some of the recent controversies about conflicts of interest in case selection or recusals, but, especially with the accompanying Commentary, it is clearer than the current ethics and recusal procedures which, as with many procedures governing the institution, are mostly known among those who practice before the Court.

Some of this guidance is specific (e.g., Canon 4.1.d, which says: “A Justice may attend a ‘fundraising event’ of law-related or other nonprofit organizations, but a Justice should not knowingly be a speaker, a guest of honor, or featured on the program of such event. In general, an event is a ‘fundraising event’ if proceeds from the event exceed its costs or if donations are solicited in connection with the event.”), and some is very general. For example, the introduction to Canon 4 itself says: “A Justice may engage in extrajudicial activities, including law-related pursuits and civic, charitable, educational, religious, social, financial, fiduciary, and government activities, and may speak, write, lecture, and teach on both law-related and nonlegal subjects. However, a Justice should not participate in extrajudicial activities that detract from the dignity of the Justice’s office, interfere with the performance of the Justice’s official duties, reflect adversely on the Justice’s impartiality, lead to frequent disqualification, or violate the limitations set forth below.”

Thus, for example, Justice Ginsburg can not only speak about opera but appear in one as well, even if donations to the opera are solicited (as they almost always are).

CONGRESS

Bipartisan Votes in House Administration Committee Advances Small Bills to Improve Election Administration: Roll Call predicts the big American Confidence in Elections bill, which logrolled 50 bills into one, is stalled, but reports that the House Admin Committee advanced several smaller bills with bipartisan votes on Nov. 30. “On bipartisan votes, the committee advanced legislation to protect election observer access and to protect against the influence of foreign nationals in elections, a legislative recommendation made by the bipartisan Federal Election Commission.”

DoJ

New Department of Justice Guidelines on Criminal Investigations of Congressional Offices: On Nov. 7, Deputy Attorney General Lisa Monaco released a new memorandum updating its policies and procedures for criminal investigations involving Members of Congress and congressional staff. The DoJ Office of Public Integrity (which has had some interesting past dealings with tax-exempt public policy advocacy organizations) offers these “clarifications” (often better described as tightening central control) of its procedures to remind prosecutors of the necessary reviews and steps required to balance various Executive Branch interests against those of the Legislative Branch. More info from Covington, Ballard, Bloomberg Law.

More Reporting on Chinese Police Operating Worldwide, Multi-Billion Dollar Coercion Campaign Against Critics of CCP: CNN has a deep dive into a global social media effort led by Chinese Police coercing and harassing those who complain about the Chinese Communist Party or its activities in the United States and elsewhere. In April, the U.S. Department of Justice filed multiple indictments against those operating Chinese “police stations” in the U.S.

Known as “Spamouflage” or “Dragonbridge,” the network’s hundreds of thousands of accounts spread across every major social media platform have not only harassed Americans who have criticized the Chinese Communist Party, but have also sought to discredit US politicians, disparage American companies at odds with China’s interests and hijack online conversations around the globe that could portray the CCP in a negative light. …

Experts who track online influence campaigns say there are signs of a shift in China’s strategy in recent years. In the past, the Spamouflage network mostly focused on issues domestically relevant to China. However, more recently, accounts tied to the group have been stoking controversy around global issues, including developments in the United States. …

Jiajun Qiu, whose academic work focused on elections and who fled China in 2016, showed CNN what happens when he types his name into X, formerly known as Twitter. There are sometimes dozens of accounts pretending to be him by using his name and photo. They are designed by the operators of Spamouflage, Linvill explained, to confuse people and prevent them from finding Qiu’s real account by muddying the waters. Now living in Virginia, Qiu runs a pro-democracy YouTube channel and has faced an onslaught of homophobic, racist and bizarre insults from social media accounts that Linvill’s team and others have tied to Spamouflage. Some accounts have posted cartoons that convey Qiu as an insect working on behalf of the US government. Another image depicts him being stomped by a cartoon Jesus. Yet another paints him as a dog on the leash of an American rat.

Not mentioned in the CNN article were the two amicus briefs filed in Americans for Prosperity Foundation v. Bonta, the 2021 donor disclosure case in which the Supreme Court shut down the California Attorney General’s “dragnet” collection of exempt organization donor information. The briefs from both Citizens Power Initiatives for China, and China Aid Association paint chilling pictures of a sweeping worldwide hacking, apprehension and repression initiative that creates terror in millions of overseas Chinese, which can be triggered by leaks or publication from IRS, FEC or other governmental reporting. Some of the examples from the Citizens Power brief include: “From time to time, amicus Citizen Power Initiatives’ website is offline due to cyber attacks. [Id., at 5 n. 2] … on August 22, 2019, the Chinese Foreign Ministry sent a 42-page dossier to various international media outlets concerning Hong Kong’s ‘anti-extradition bill’ protests. That dossier smeared Citizen Power Initiatives, its interethnic interfaith leadership conferences, and its founder and president, Dr. Yang Jianli.” Id., at 6, CPI’s response to the dossier here.

GENERAL

Strange Bedfellows Success – Bari Weiss Gives Barbara Olson Memorial Lecture to Standing Ovation From Federalist Society Convention: To quote former (and now estranged) New York Times Editor Bari Weiss from her surprisingly-successful appearance before the convention of the Federalist Society:

When Gene Meyer gave me a list of the people who had previously given the Barbara Olson lecture, I was sure you guys had made a mistake in inviting me. I am not a lawyer or a legal scholar or a former attorney general. I have, in my time, edited dozens of op-eds about Chevron deference, but I’m still not quite sure what that means.

Nor am I a member of the Federalist Society. My parents, who probably couldn’t afford the local country club, raised us on the Groucho Marx line: I don’t want to belong to any club that would have me as a member.

Then there’s the question of my politics. I hear you guys are conservative. Forgive me, then: I’d like to begin by acknowledging that we are standing on the ancestral, indigenous land of Leonard Leo. ProPublica tells me that Washington is his turf.

Then I googled Barbara Olson. …

In recognizing allies, I’ll be an example. I am a gay woman who is moderately pro-choice. I know there are some in this room who do not believe my marriage should have been legal. And that’s okay, because we are all Americans who want lower taxes.

According to Law Prof. Josh Blackmun:

The Olson lecture at the 2023 Convention will always stand out in my memory. … Yet, my confusion quickly dissipated. Bari delivered a rousing, timely, and penetrating speech. Bari spoke to our current moment, including the conflict in Israel and attempts to destroy our own civilization. She formed a common kinship with those she disagrees with – especially a FedSoc crowd. And she connected with everyone in that room. At the end, the room was silent. You could hear a Madison lapel pin drop. When Bari concluded, the standing ovation lasted for nearly ninety seconds. (It was the longest one I could remember following an Olson lecture.)

You must be logged in to post a comment.